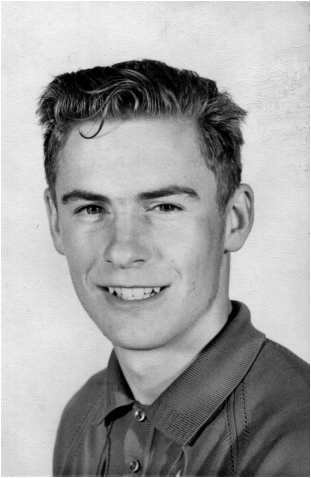

James E Southern (known as Jim in Australia, N.Z., and South Africa)

James E Southern (known as Jim in Australia, N.Z., and South Africa)

Twenty Years

Around the World

“I’m going to make it!” Finally a car had stopped for us. I was hitchhiking through Yugoslavia with a couple I had met a few days earlier. After Yugoslavia it would be easier hitchhiking to Belgium from where I planned to catch the ferry to England. I had lived in England as a child twenty years earlier.

We arrived that evening in Ljubljana. In our search for someone who could speak English and somewhere to spend the night, we ended up at the university. An English speaking resident of a university dormitory lent us her room for the night. She spent the night elsewhere.

Her room was small but comfortable. Before settling down to sleep, we smoked a few joints. When high, however, I tended to worry. Here we were in a Communist country doing something illegal. Perhaps there was a hidden microphone in the room, with someone listening in who could understand English, someone otherwise so difficult to find. Perhaps the secret police were already sniffing at the keyhole of the door to our room.

What is right? What is wrong? Had I, in my twenty-three years in this world, done more good than harm? A Marxist motto is “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” Having lived most of my life in affluent countries, I had received more than the average person in this world. But had I given to the best of my ability? Probably not. I had thought more of fulfilling my own desires. The student who had lent us her room, during our brief discussion on economics, had inferred that we capitalists were living high at the expense of the poor. I reflected on my life.

One of my first memories is of trying to float down a stream in a washtub. I might have been three years old at the time. The stream was at the back of my grandparents’ property in Milford-on-sea in southern England. I had stopped to get a stick to push myself away from the shallows, but my grandfather saw me and took the washtub away from me. If only I hadn’t stopped I might have gotten out of sight around the bend and on my way to the sea!

We arrived that evening in Ljubljana. In our search for someone who could speak English and somewhere to spend the night, we ended up at the university. An English speaking resident of a university dormitory lent us her room for the night. She spent the night elsewhere.

Her room was small but comfortable. Before settling down to sleep, we smoked a few joints. When high, however, I tended to worry. Here we were in a Communist country doing something illegal. Perhaps there was a hidden microphone in the room, with someone listening in who could understand English, someone otherwise so difficult to find. Perhaps the secret police were already sniffing at the keyhole of the door to our room.

What is right? What is wrong? Had I, in my twenty-three years in this world, done more good than harm? A Marxist motto is “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” Having lived most of my life in affluent countries, I had received more than the average person in this world. But had I given to the best of my ability? Probably not. I had thought more of fulfilling my own desires. The student who had lent us her room, during our brief discussion on economics, had inferred that we capitalists were living high at the expense of the poor. I reflected on my life.

One of my first memories is of trying to float down a stream in a washtub. I might have been three years old at the time. The stream was at the back of my grandparents’ property in Milford-on-sea in southern England. I had stopped to get a stick to push myself away from the shallows, but my grandfather saw me and took the washtub away from me. If only I hadn’t stopped I might have gotten out of sight around the bend and on my way to the sea!

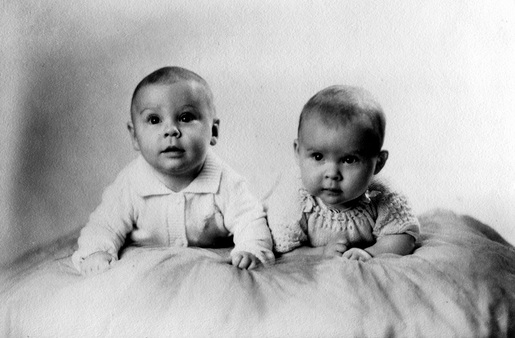

I had a twin sister, Sue. We and our widowed mother were living with our grandparents—our mother’s parents. Sue and I had been born in Canada during the war. After the war, in 1945, our mother, with us twins, returned to live in England.

In England single men were scarce, but our mother found one, a handsome Englishman on holiday in England. I remember the wedding and Sue and I having to hold up the end of a long train on our mother’s bridal gown. “Why make a train so long that it needs holding up? What use are trains anyway?”

After the wedding we set off for Patagonia where our stepfather had been living for most of his life. We flew to Lisbon and then Dakar from where we would cross the Atlantic. I remember an incident in Dakar, helped by Mom reminding us about it.

Mom and our new dad were dining in a café beside the airport terminal. Sue and I were bored so Mom allowed us to wait outside. It was evening—dark if it hadn’t been for a full moon. Some local children were playing shadow tag by moonlight. Sue and I joined them, running around trying to keep our shadows from being stepped on. But then Mom found us and scolded us for not staying near the cafe. Other passengers had already boarded the plane.

We flew from Dakar to Recife and then Rio de Janeiro where Mom and Dad stopped for their honeymoon. From Rio de Janeiro we flew to Buenos Aires and on to Rio Gallegos in southern Patagonia.

The border between Argentina and Chile runs to the southeastern tip of the South American continent. Dad had been managing a sheep ranch there, Estancia Monte Dinero. When relations worsened between Argentina and Chile, the estancia was divided, Dad buying the Chilean part and building a new house and shearing shed on the Chilean side of the fence. The fence was merely a barbwire fence through which we would climb when visiting Estancia Monte Dinero.

The wind inhibited the growth of trees. Where we were, there were only thorny calafate bushes. Because of the wind, gardens needed protection, usually windbreaks made from posts and wire with branches of calafate bushes woven between the wires. Mom had a vegetable garden. I remember a little incident.

Probably more for something for us to do, she sent Sue and I out to the cow paddock with a garden fork and a sack. We were to collect some cow patties. I found getting the patties into the sack frustrating. The dry cow patties would blow off the fork before I managed to get them into the sack that Sue was holding open. The wet ones would slip through the prongs of the fork before I got them into the sack. Or, if my aim wasn’t right, the wet ones would end up partly on Sue’s hands. In the end I found it easier just to pick up the piles by hand. The dry ones didn’t blow away. The wet ones were a bit messy.

When we got home we were sent straight to the bathroom without touching anything along the way. After the bath, I asked Mom why she wanted cow manure anyway. It was to put on the rhubarb. “But aren’t we going to eat the rhubarb?” Mom’s explanation that the manure would help the rhubarb grow, that watered-down manure would be absorbed by the rhubarb roots, put me off eating rhubarb. Mom made a joke of it, “I don’t have manure on my rhubarb. I have cream!”

Instead of our being sent to a boarding school, our aunt came to Patagonia to take us twins to a public school in Canada. We lived with her and our grandparents on our father’s side in the city that was at that time called Port Arthur in northwestern Ontario.

Having been home-schooled for the equivalent of grade 1, we started in grade 2. At the beginning of the school year, our aunt took us to the grade 2 classroom to introduce us to the teacher. Sue and I stayed in the classroom while the grade 2 students from the previous year filed in, were congratulated for graduating, then left for the grade 3 classroom. All but one left. That boy must have felt a kinship with us, the three of us waiting for the former grade 1 students to file into their new classroom. He became my best friend. It wasn’t until years later that I realized he had failed grade 2.

Those four years living with my aunt and grandparents were the happiest years of my life. I remember particularly the summer months spent at a log cabin by a lake, fishing and boating and exploring the woods.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, our stepfather was coming to a decision. Probably as a result of our mother’s persuasion, he sold the estancia in preparation for moving to Canada. Perhaps also he sensed the unstable political situation in Chile. The Englishman to whom he sold the ranch lost it when Allende came to power, taking the land away from the rich landowners and giving it to the people.

Ranching in Canada, however, requires different tactics from ranching in Patagonia. Dad soon lost his wealth. Sue and I, having joined them on the farm where they ended up in southern Alberta, replaced the hired hand and the housemaid. By this time we had two brothers and a sister. We had to skip school sometimes to work on the farm—lambing time, shearing time, and sometimes for haying. One day I stayed home from school to be a fence to keep the sheep from grazing a crop of oats, I think it was, that was beginning to grow.

I claim to have started the fad of wearing worn-out blue jeans. During the late fifties, teenage boys in our school wore dress pants unless they were planning to play some sport or another during lunch break. I went to school wearing the pair of blue jeans that showed the minimum amount of wear and tear.

I didn’t do as well as Sue in the grade 12 departmental exams. She went on to university while I went to grade 13 in Ontario. That was the first time Sue and I had been separated for any length of time. Before then it had been us twins and the rest of the world. It became just me and the rest of the world.

To represent the new me, I started calling myself “Jim” instead of “James.” But it didn’t help. I had hoped that getting away from the farm would set my life right again. It was discouraging to discover that my problems were within me.

One thing that I now consider to have been positive was my association with Christians while attending Port Arthur Collegiate Institute and, the next year, Lakehead College. I didn’t consider Christianity to be for me, but I did appreciate being included with a group of friends.

After failing every one of my subjects that first year at Lakehead College, I was feeling depressed, and considering ending it all. Then I made a decision. Since I was still young, I would see more of life—work my way around the world—and then decide what to do.

My stepfather, on learning that I had decided not to return to college, paid my plane fare from Port Arthur to Calgary in order for me to come to help look after the farm while he and my mother visited England for a couple of months. Sue, before she returned to university, and our oldest half-brother and I managed well enough except for a tractor accident and a pack of dogs killing some sheep.

When they returned from England, I could continue my around-the-world voyage. Dad gave me a ride to the Trans-Canada Highway and I set off hitchhiking westward, a duffle bag in one hand and a black suitcase in the other. Over the next couple of years I reduced my luggage to just that one black suitcase.

Arriving on the west coast, I contacted a cousin. Dale and his friend Wayne, a fellow art school student, were living in Dale’s parents’ home while his parents were away—an ideal living situation for young people who liked to do their own thing. Dale invited me to join them. Years later I was talking to a Japanese Canadian student at a Tokyo University. Upon learning that he was from Vancouver and had been a student at the Vancouver School of Art, I asked him if he happened to know my cousin and his friend. “Those two! The two craziest guys in the school!”

I had hoped to get work on some ship sailing out of Vancouver, but found they weren’t particularly interested in hiring someone with no experience, no connections, and no union membership. Perhaps I also came across as someone who was somewhat unsure of himself.

Having earned a little money working a temporary job, I put my name down as a paying passenger on a standby list at the P&O-Orient office. One morning in January I got a phone call. There was a berth available from Vancouver to Auckland on the Arcadia leaving that afternoon. Did I want to take it?

I did. I packed my things, left a note for my cousin, caught a taxi to the P&O-Orient office, and bought a ticket to New Zealand, paying $497. I know the exact amount as I had started keeping a record of all earnings and expenses, a record that I would keep for most of the rest of my life. It served as sort of a diary as wherever I went I usually spent something.

From Vancouver we sailed to San Francisco, to Los Angeles, to Honolulu, to Suva, and then to Auckland. I didn’t patronize the bars on board ship as I had little money. I did hang around the swimming pool too long on a hot afternoon and got sunburnt. Life on a luxury cruise wasn’t for me what it is made out to be. Months later, in New Zealand, I overheard someone saying he had come to New Zealand on the Arcadia. Finding out that it was the same sailing that I had been on, I told him so. He had trouble believing me as he hadn’t seen me in the bars or at the parties.

It has been said that New Zealand is more British than Britain, so I thought, having lived in England as a child, that it wouldn’t be foreign to me. However, that first day in Auckland taught me that I wasn’t as British as I had imagined. I had checked in to a hostel where meals were provided. The manageress told me that tea was at 5 o‘clock. I told her that I ordinarily didn’t bother with tea, but asked her when supper was. She told me that they ordinarily didn’t bother with supper, but I could help myself to a snack from the refrigerator. After a bit more discussion I realized that what she was calling “tea” I was calling “supper.” I was later to learn that they call supper “tea” also in Australia and parts of England and Ireland.

At that time foreigners didn’t need work permits. Jobs in New Zealand were easy to find. In fact, so I was told, the only two people unemployed were the two who worked in the unemployment bureau. There was a newspaper ad for a labourer in a soft drink factory. In the heat of the day that seemed appealing, so I went for an interview and got the job. I was to start the next day. However that same day I met a guy from the ship, Grant by name, who was heading for the South Island to pick fruit. That seemed more appealing. So I returned to the factory, telling them that I had changed my mind, and the next day Grant and I headed south by train. Changing the last of my Canadian dollars into New Zealand pounds gave me enough for the train fare, the ferry to the South Island, and the bus to Nelson.

Getting off the bus in Nelson, we were approached by a man asking if we wanted to pick tobacco. Why not? If we had known that it was harder work than picking fruit we might have declined. He drove us to his tobacco farm. The other workers were young Maoris in good shape. After our first day of picking tobacco, Grant and I were stretched out on our beds exhausted while the Maoris were outside kicking around a football.

After a couple of weeks, Grant and I were able to do more than just rest after a day’s work. I went with the Maoris to a dance hall one evening. However we weren’t dancing. We were drinking beer in the car outside the dance hall. The police caught us. They were nice about it though, giving us the choice of two fines, “drinking while under age” or “drinking in a public place.” Both fines were for the same amount. We chose “drinking in a public place.”

The frost came and tobacco picking ended. Grant and I caught a bus to Christchurch where I answered an ad for Nassella Tussock grubbers. The Nassella Tussock is an imported tussock grass originally planted along the Waipara River banks to control erosion. It spread around the North Canterbury Plain, choking out good grazing grass. The Regional Pest Management Society was hiring gangs of men with hoes to roam the hills and valleys grubbing out the tussocks. I joined one of those gangs. It was great exercise, more pleasant than picking tobacco.

Evenings, Sundays, and rainy days back at the camp were entertaining. A fellow grubber had been a culler. He told of shooting deer and feral goats and pigs. He would cut off the tails to collect the bounty on them, leaving the carcasses to rot. As well as the Nassella Tussock grass, New Zealand had a problem with non-native animals multiplying excessively.

Nassella Tussock grubbing was a job that the government arranged for convicts getting out of prison. There were a number of ex-cons at the camp. One ex-con, while in prison, used to tattoo fellow inmates—anyone who wanted a tattoo. My roommate, on hearing this, wanted a tattoo. So he lay on his back on a dining room table drinking lots of beer to prepare for the ordeal while the cook drew a tiger on his chest. Then the ex-con set to work tattooing, using a needle and thread that I had lent him and a bottle of ink. Perspiration was dripping off my roommate’s forehead. Finally he couldn’t take the pain any longer and asked if the tattoo could be finished the following evening.

The next morning my roommate didn’t get up to go to work. He was sick. When I returned from work at the end of the day, he and his belongings were no longer in our room. I learned that he had been taken to hospital with blood poisoning. In the hospital they discovered that he was AWOL (away without leave) from the army. After the hospital he was going to be sent to a military prison. I wonder if he still has a half-finished, lopsided tiger on his chest.

After quitting Nassella Tussock grubbing, I returned to Christchurch. On my twenty-first birthday I was in a pub with some friends. I hadn’t told anyone that it was my birthday as it was the custom, so I was told, for the birthday boy to buy drinks for his friends. The pub manager came up to me asking if I was of drinking age. This was late afternoon. (I know that it couldn’t have been evening as pubs closed at 6 p.m. in those days.) I had been born in the morning seventeen time zones away. In Port Arthur it was still night. So I was a few hours short of turning 21! When under interrogation it is not good to be hesitant. “Yes,” I asserted. He believed me.

I decided to travel on to Australia. The Oriana would be sailing from Wellington in six week’s time, so I returned to the North Island, got a temporary job in Wellington packing up the contents of a textile factory that was moving, then sailed for Sydney. I had to smuggle out all the New Zealand pounds that I had saved as we were supposed to take only a limited amount of New Zealand currency out of the country.

After a few days in Sydney I caught a bus to Surfers Paradise in Queensland. I didn’t surf but I did work mixing mortar for bricklayers building a hotel. It was in Surfers Paradise that I met a nice Kiwi girl on holiday in Australia. We parted ways when she had to return to New Zealand but I wanted to see more of Australia. Looking back on it now, New Zealand wouldn’t have been a bad country in which to have lived for the rest of my life.

Hitchhiking north from Surfers Paradise, I was picked up by a Pommy. That’s what Aussies call an Englishman. We were both looking for work, and found work in Yungaburra, North Queensland, helping build a plywood mill. Payday was a time for celebration. In Australia, unlike New Zealand, pubs closed late in the evening. After pub closing this particular evening, I remember helping my friend, with the bartender under his other arm, to his car. Then he drove us back to the boarding house where we were staying.

After Yungaburra, I travelled around Queensland before heading for the outback. Hitchhiking in the outback is difficult as towns are few and far between and most vehicles travelling a fair distance are already full. I was later to meet an American who told me he had camped outside Mt. Isa for eight days. Each day a tour bus would pass him. He could overhear the tour guide telling the tourists, “This hitchhiker has been here five days.” Then, the next day, “This hitchhiker has been here six days.” Then . . . .

I caught a ride that first day from Mt. Isa to Camooweal bordering the Northern Territory. The next day, waiting beside the highway outside Camooweal, I got picked up by a Canadian with his Aussie girlfriend. However, they weren’t going far. They were going spelunking near Camooweal, and invited me to join them.

We descended by rope into a hole in the ground. It was nice and cool down there, compared to the heat on the surface. The rope was just for the first part. We climbed without ropes down to the water table level. The Aussie went swimming, inviting me to join her. I declined. The water was cold! On the ascent I was longing to return to the surface where it was nice and warm.

I slept that night on the porch of one of the two pubs in the town. That was after closing. Before closing, I was entertained, for example, by one of the locals vomiting over the railings of the porch, projecting his vomit at least three yards before it hit the ground.

The third evening I hung out at the other pub. Beside it was a petrol station where vehicles filled up before travelling on. At the pub I met a somewhat inebriated man with his German Shepherd. He was also wanting to travel on. Both of us would stagger out to ask for a ride when any vehicle stopped at the petrol station. No one gave us a ride, and that without them even knowing that there were actually three of us, not just two.

My new friend said he had a taxi driver friend in Tennant Creek, which I later learned was three hundred miles down the road. He phoned him. Yes, he would come and pick us up. About four hours later he arrived. On learning that there was a dog also, he refused to take us. But my friend was persuasive. The tax driver relented, saying that if the dog got sick he would be charging extra. “Extra?” I wondered as the dog and I got in the back of the taxi. I had thought this was a friendship arrangement—a free ride.

The dog did get sick. The taxi driver did charge extra. My friend didn’t have any money, having spent the last of it on beer and the long distance phone call to Tennant Creek. I didn’t have any option. I paid. No worry, my friend told me, we could earn big money at Peko Mines near Tennant Creek. So we went there. I got hired as mill operator in the mill on the surface. We were milling copper ore. It was hot and noisy there in the mill. At that time only sissies wore ear protection. My hearing got permanently impaired.

At Peko Mines there were about four hundred of us “lonely bachelors” as we were described in a newspaper article in South Australia. A sheila, as Aussies call a woman, responded in a letter to us there at the mine saying she would be willing to come to keep us company if she could get to Tennant Creek. Raffle tickets were sold to almost everyone at the mine to raise money for her airfare. The lucky winner, however, was one of the few men who already had a girlfriend in Tennant Creek. So he sold his ticket to the highest bidder.

I worked six months at Peko Mines, long enough to claim the tax discount for working in the Northern Territory. Then I travelled on, first visiting Alice Springs from where I sent postcards to friends and relatives in Canada and England. Heading back north, I got stuck for a while, along with three other hitchhikers, at Three Ways. Finally a truck stopped. The driver bargained with us—£10 for a ride to Darwin in the back of the truck. We agreed.

In Darwin I got a job with Qantas Airways. Pilot? No, dishwasher. The job was mostly washing dishes from the various planes on their Darwin stopover. At that time airline companies served meals on proper plates with silverware and real glasses. The dirty dishes, and plates of food that hadn’t been served at all, were taken off the planes and new plates of food provided. All food that was taken off the planes was incinerated—government regulation because of the possibility of introducing unwanted parasites or something into Australia.

The new Qantas barracks were the nicest in town, but we didn’t have a kitchen and dining room there. When we didn’t eat at the airport, we ate at the Commonwealth barracks across the street from the Qantas barracks. At the Commonwealth barracks various government officials lived and ate. At a table where I often sat, I shared my dream of working on a ship to see more of the world. A customs official told me that the captain of a Norwegian oil tanker in port right at that moment was looking for extra crew members. When it came to taking action to realize my dream, I was hesitant. If I stayed two years with Qantas I could get a discount on air travel. I didn’t go to see the captain.

The next day at lunch the customs official asked me if I had seen the captain. “No.” He said the captain was still looking for extra crew members. So I went to see the captain. I got hired. I returned to the Qantas barracks and packed up my things, also letting the Qantas office know that I was quitting. Early the next morning I was on board the M/T Marie Eline. Breaking out of a comfortable rut can be traumatic. As we sailed away my hands grasping the ship rails were trembling.

I was hired as an oiler or greaser in the engine room. But my main job was helping paint the engine room. We started at the top. The top of the engine room is the hottest part of the engine room. The engine room is the hottest part of the ship. The vicinity of the equator is the hottest part of the world. It was hot!

We stopped in Balikpapan, Indonesia, to pick up oil. I joined the Norwegians going into town in the evening. They drank imported beer whereas I tried the local brew which was a lot cheaper. However, it tasted awful. Consequently I didn’t drink much. Consequently I wasn’t so drunk. Consequently I could bargain with the taxi driver who was taking us back to the ship so we didn’t get ripped off as much as we might have otherwise.

From Balikpapan we headed north as though we were going somewhere other than Singapore. At that time relations between Indonesia and Singapore were strained so we weren’t supposed to take Indonesian oil to the refineries in Singapore. But then we turned around and headed south around Borneo as that was the shortest way to Singapore.

When we sailed from Singapore, my Kiwi cabin-mate was not in our cabin. In fact, he was not on the ship. He had missed the boat. We sailed back to Borneo, but this time to Miri to pick up oil. On our return to Singapore, my cabin-mate was taken onto the ship by the Singapore authorities, having spent the time while we were away in jail. He had missed the sailing, being too much involved with a nice Singapore girl.

I had decided to leave ship in Singapore as the M/T Marie Eline was sailing to the Persian Gulf whereas I wanted to see more of the Far East. The first mate had to spend half a day with me at various offices ashore before I was allowed to disembark.

Apart from my stay on the Norwegian oil tanker, Singapore was my first experience alone in a non-English culture. It was somewhat of a culture shock, even though Singapore has a strong British heritage. Shop owners picked up on my naivety. They would invite me into their shops to look around even though I had said that I wasn’t planning on buying anything. When inside, I accepted their occasional offer of a free soft drink. That made me feel obliged to buy something in return for their favour. After a few years of travelling, I would become more cynical and write as one of my Tips for Travellers, ”When passing street vendors or shop owners in the doors of their shops, don’t let them catch your eye. Turn your attention elsewhere.”

One of the requirements before being allowed to stay in Singapore was to buy a ticket out of Singapore. I bought a ticket to Japan on the Laos, a Messageries Maritimes cargo/passenger ship. The return portion of the ticket was on another Messageries Maritimes ship leaving Yokohama a month and a half later.

We sailed from Singapore to Saigon. This was in 1965, during the Vietnamese war. At that time the main influence of the war on Saigon was the great influx of foreigners in the city. There was a curfew that lasted only for the evenings. At midnight, I think it was, people were again allowed out on the streets. I spent the evening with a couple of Kiwis from the ship in a bar in Saigon. The girls hanging around the bar pressed us to buy drinks for them. We refused, knowing that they would be served only coloured water. After a while the girls ignored us. At midnight, or whenever it was that the curfew was lifted, we returned to the ship.

From Saigon we sailed to Hong Kong. When showing slides of my travels and showing street scenes of Hong Kong, people sometimes ask what the special occasion was. They think there must have been a celebration or something for the sidewalks to be that crowded. “No,” I tell them. “That’s just the way it is.”

From Hong Kong we sailed for Kobe, Japan, where I disembarked. I remember my first meal at a sidewalk café, being given disposable chopsticks. At first I thought it was just one stick but it was two joined together. In order to use them, they needed to be broken apart. So I learned how to eat with chopsticks.

I didn’t try hitchhiking in Japan as the Japanese weren’t familiar with it. A fellow traveller told me that when he and his friend were hitchhiking in Japan a man picked them up who couldn’t speak English. They pointed out on a map where they wanted to go and he drove them there. Actually they were wanting to go right across Japan and had just picked out the next town on the map. They wondered if he was going further. They pointed on the map to the next town. He drove them there, then on to the next town where the two got out of the car. They had realized that he was driving out of his way for them.

I caught a train to Kyoto, arriving late in the evening. No one at the train station spoke English. Finally an English-speaking lady was summoned. She took me to a rooming house for foreign students where I ended up staying for most of the time that I was in Japan. It was not only the beauty of the city that held me there, but the high cost of travelling and, more subconsciously, my tendency to hang on to something that was somewhat familiar.

I remember my first time at an ofuro, a public bath. One of the students at the rooming house where I was staying had earlier pointed out the men’s door to the ofuro. I went through that door. There I encountered some Japanese women. Had I gone through the wrong door? No, they were collecting the admission fee and renting towels and selling soap to those who hadn’t brought their own towels and soap. Where was I to undress and leave my clothes? There by some shelves near the admission booth. I felt self-conscious undressing in front of the women but they discreetly looked away.

Then I went through a glass door to the first chamber where I washed myself and rinsed off the soap by pouring water over myself with a bowl. Then I entered the bath area. The bath was a large semi-circular pool. At one time it had been a circular pool but a wall had been built bisecting it. On the other side of the wall was the women’s pool. A dozen or so Japanese men, up to their necks in the bath, watched me as I tested the water. It was hot! My foot, when I withdrew it, was red. I had been told that easing in was easier than rushing in. I tried easing in but got only as far as my knees before rushing out.

In a corner of the room was a bath of icewater. I couldn’t waste my admission fee by only having washed myself. I got into the bath. It was cold! After a while the thought of going into the hot pool was very appealing. I got out and easily waded into the hot pool right out to my neck, joining the dignified Japanese men. After a while I began feeling a bit too hot. Moving would disturb the slightly cooler layer of water on the surface of my skin. But I couldn’t stand it any longer. I rushed out and jumped into the icewater. Nice and cool! After a while I felt too cool. I returned to the hot pool. After a while I felt too hot. I returned to the cool tub. The third time time that I returned to the hot pool all the other men left en mass. I wondered if I had offended them somehow, or if it was closing time or something. Now I think that they couldn’t control their laughter and it didn't want me to see them laughing.

A few days before my ship was due to sail from Yokohama, I took the train to Tokyo, staying in a youth hostel there. Through various connections, I ended up hanging around with some university students. Students were often wanting to practise speaking English, particularly young schoolgirls who often also wanted to have their photo taken with me. The university students introduced me to the Japanese Canadian who had been to the Vancouver School of Art with my cousin and his friend.

I boarded the SS Viet-Nam in Yokohama and we sailed first to Hong Kong, then to Manila, then to Saigon, and on to Bangkok, Thailand. I disembarked in Bangkok, forfeiting the Bangkok to Singapore portion of my ticket. I was planning on joining some fellow travellers going to a Thai beach to celebrate Christmas.

It was in Bangkok that I had my first experience smoking hashish. Afterwards, on our way back to the Thai Song Greet Hotel where we were staying, I got separated from the others when they crossed a busy street to catch a bus on the other side. I hesitated, finding it difficult to judge how much time I needed to dash across the street in front of approaching traffic. The bus left without me. Then I got worried—paranoid to be exact. I thought men were following me, wanting me to lead them back to our hotel. I determined not to betray my friends.

The taxi which I caught was involved in a fender-bender. Naturally I thought it was purposeful. That solidified my resolve not to return to our hotel. So I spent the rest of the night in another hotel, sitting in a chair in my room as, for a reason I don’t remember, I didn’t want to use the bed.

I spent the next day eluding the men who I thought were following me. By the end of the day I thought I had eluded them, or else my paranoia had worn off. I returned to our hotel to find only my luggage in the room. The others had left for the beach. Since I couldn’t remember which beach it was that they were going to, I abandoned the idea of joining them.

The next morning I caught a taxi to the airport north of Bangkok. From there I planned to hitchhike north. However, hitchhiking proved difficult. Thais weren’t accustomed to hitchhikers. When going to the airport terminal to use the facilities there, I got talking to a young Thai who could speak English. “Isn’t this a special day for you Christians?” Responding to my puzzled look he continued, “Isn’t it Chris....” Only then did I realize it was Christmas.

The young Thai invited me to his home after his working day was over. The next morning I accompanied him back to the airport and again stationed myself by the highway heading north. This time I got a ride.

In England single men were scarce, but our mother found one, a handsome Englishman on holiday in England. I remember the wedding and Sue and I having to hold up the end of a long train on our mother’s bridal gown. “Why make a train so long that it needs holding up? What use are trains anyway?”

After the wedding we set off for Patagonia where our stepfather had been living for most of his life. We flew to Lisbon and then Dakar from where we would cross the Atlantic. I remember an incident in Dakar, helped by Mom reminding us about it.

Mom and our new dad were dining in a café beside the airport terminal. Sue and I were bored so Mom allowed us to wait outside. It was evening—dark if it hadn’t been for a full moon. Some local children were playing shadow tag by moonlight. Sue and I joined them, running around trying to keep our shadows from being stepped on. But then Mom found us and scolded us for not staying near the cafe. Other passengers had already boarded the plane.

We flew from Dakar to Recife and then Rio de Janeiro where Mom and Dad stopped for their honeymoon. From Rio de Janeiro we flew to Buenos Aires and on to Rio Gallegos in southern Patagonia.

The border between Argentina and Chile runs to the southeastern tip of the South American continent. Dad had been managing a sheep ranch there, Estancia Monte Dinero. When relations worsened between Argentina and Chile, the estancia was divided, Dad buying the Chilean part and building a new house and shearing shed on the Chilean side of the fence. The fence was merely a barbwire fence through which we would climb when visiting Estancia Monte Dinero.

The wind inhibited the growth of trees. Where we were, there were only thorny calafate bushes. Because of the wind, gardens needed protection, usually windbreaks made from posts and wire with branches of calafate bushes woven between the wires. Mom had a vegetable garden. I remember a little incident.

Probably more for something for us to do, she sent Sue and I out to the cow paddock with a garden fork and a sack. We were to collect some cow patties. I found getting the patties into the sack frustrating. The dry cow patties would blow off the fork before I managed to get them into the sack that Sue was holding open. The wet ones would slip through the prongs of the fork before I got them into the sack. Or, if my aim wasn’t right, the wet ones would end up partly on Sue’s hands. In the end I found it easier just to pick up the piles by hand. The dry ones didn’t blow away. The wet ones were a bit messy.

When we got home we were sent straight to the bathroom without touching anything along the way. After the bath, I asked Mom why she wanted cow manure anyway. It was to put on the rhubarb. “But aren’t we going to eat the rhubarb?” Mom’s explanation that the manure would help the rhubarb grow, that watered-down manure would be absorbed by the rhubarb roots, put me off eating rhubarb. Mom made a joke of it, “I don’t have manure on my rhubarb. I have cream!”

Instead of our being sent to a boarding school, our aunt came to Patagonia to take us twins to a public school in Canada. We lived with her and our grandparents on our father’s side in the city that was at that time called Port Arthur in northwestern Ontario.

Having been home-schooled for the equivalent of grade 1, we started in grade 2. At the beginning of the school year, our aunt took us to the grade 2 classroom to introduce us to the teacher. Sue and I stayed in the classroom while the grade 2 students from the previous year filed in, were congratulated for graduating, then left for the grade 3 classroom. All but one left. That boy must have felt a kinship with us, the three of us waiting for the former grade 1 students to file into their new classroom. He became my best friend. It wasn’t until years later that I realized he had failed grade 2.

Those four years living with my aunt and grandparents were the happiest years of my life. I remember particularly the summer months spent at a log cabin by a lake, fishing and boating and exploring the woods.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, our stepfather was coming to a decision. Probably as a result of our mother’s persuasion, he sold the estancia in preparation for moving to Canada. Perhaps also he sensed the unstable political situation in Chile. The Englishman to whom he sold the ranch lost it when Allende came to power, taking the land away from the rich landowners and giving it to the people.

Ranching in Canada, however, requires different tactics from ranching in Patagonia. Dad soon lost his wealth. Sue and I, having joined them on the farm where they ended up in southern Alberta, replaced the hired hand and the housemaid. By this time we had two brothers and a sister. We had to skip school sometimes to work on the farm—lambing time, shearing time, and sometimes for haying. One day I stayed home from school to be a fence to keep the sheep from grazing a crop of oats, I think it was, that was beginning to grow.

I claim to have started the fad of wearing worn-out blue jeans. During the late fifties, teenage boys in our school wore dress pants unless they were planning to play some sport or another during lunch break. I went to school wearing the pair of blue jeans that showed the minimum amount of wear and tear.

I didn’t do as well as Sue in the grade 12 departmental exams. She went on to university while I went to grade 13 in Ontario. That was the first time Sue and I had been separated for any length of time. Before then it had been us twins and the rest of the world. It became just me and the rest of the world.

To represent the new me, I started calling myself “Jim” instead of “James.” But it didn’t help. I had hoped that getting away from the farm would set my life right again. It was discouraging to discover that my problems were within me.

One thing that I now consider to have been positive was my association with Christians while attending Port Arthur Collegiate Institute and, the next year, Lakehead College. I didn’t consider Christianity to be for me, but I did appreciate being included with a group of friends.

After failing every one of my subjects that first year at Lakehead College, I was feeling depressed, and considering ending it all. Then I made a decision. Since I was still young, I would see more of life—work my way around the world—and then decide what to do.

My stepfather, on learning that I had decided not to return to college, paid my plane fare from Port Arthur to Calgary in order for me to come to help look after the farm while he and my mother visited England for a couple of months. Sue, before she returned to university, and our oldest half-brother and I managed well enough except for a tractor accident and a pack of dogs killing some sheep.

When they returned from England, I could continue my around-the-world voyage. Dad gave me a ride to the Trans-Canada Highway and I set off hitchhiking westward, a duffle bag in one hand and a black suitcase in the other. Over the next couple of years I reduced my luggage to just that one black suitcase.

Arriving on the west coast, I contacted a cousin. Dale and his friend Wayne, a fellow art school student, were living in Dale’s parents’ home while his parents were away—an ideal living situation for young people who liked to do their own thing. Dale invited me to join them. Years later I was talking to a Japanese Canadian student at a Tokyo University. Upon learning that he was from Vancouver and had been a student at the Vancouver School of Art, I asked him if he happened to know my cousin and his friend. “Those two! The two craziest guys in the school!”

I had hoped to get work on some ship sailing out of Vancouver, but found they weren’t particularly interested in hiring someone with no experience, no connections, and no union membership. Perhaps I also came across as someone who was somewhat unsure of himself.

Having earned a little money working a temporary job, I put my name down as a paying passenger on a standby list at the P&O-Orient office. One morning in January I got a phone call. There was a berth available from Vancouver to Auckland on the Arcadia leaving that afternoon. Did I want to take it?

I did. I packed my things, left a note for my cousin, caught a taxi to the P&O-Orient office, and bought a ticket to New Zealand, paying $497. I know the exact amount as I had started keeping a record of all earnings and expenses, a record that I would keep for most of the rest of my life. It served as sort of a diary as wherever I went I usually spent something.

From Vancouver we sailed to San Francisco, to Los Angeles, to Honolulu, to Suva, and then to Auckland. I didn’t patronize the bars on board ship as I had little money. I did hang around the swimming pool too long on a hot afternoon and got sunburnt. Life on a luxury cruise wasn’t for me what it is made out to be. Months later, in New Zealand, I overheard someone saying he had come to New Zealand on the Arcadia. Finding out that it was the same sailing that I had been on, I told him so. He had trouble believing me as he hadn’t seen me in the bars or at the parties.

It has been said that New Zealand is more British than Britain, so I thought, having lived in England as a child, that it wouldn’t be foreign to me. However, that first day in Auckland taught me that I wasn’t as British as I had imagined. I had checked in to a hostel where meals were provided. The manageress told me that tea was at 5 o‘clock. I told her that I ordinarily didn’t bother with tea, but asked her when supper was. She told me that they ordinarily didn’t bother with supper, but I could help myself to a snack from the refrigerator. After a bit more discussion I realized that what she was calling “tea” I was calling “supper.” I was later to learn that they call supper “tea” also in Australia and parts of England and Ireland.

At that time foreigners didn’t need work permits. Jobs in New Zealand were easy to find. In fact, so I was told, the only two people unemployed were the two who worked in the unemployment bureau. There was a newspaper ad for a labourer in a soft drink factory. In the heat of the day that seemed appealing, so I went for an interview and got the job. I was to start the next day. However that same day I met a guy from the ship, Grant by name, who was heading for the South Island to pick fruit. That seemed more appealing. So I returned to the factory, telling them that I had changed my mind, and the next day Grant and I headed south by train. Changing the last of my Canadian dollars into New Zealand pounds gave me enough for the train fare, the ferry to the South Island, and the bus to Nelson.

Getting off the bus in Nelson, we were approached by a man asking if we wanted to pick tobacco. Why not? If we had known that it was harder work than picking fruit we might have declined. He drove us to his tobacco farm. The other workers were young Maoris in good shape. After our first day of picking tobacco, Grant and I were stretched out on our beds exhausted while the Maoris were outside kicking around a football.

After a couple of weeks, Grant and I were able to do more than just rest after a day’s work. I went with the Maoris to a dance hall one evening. However we weren’t dancing. We were drinking beer in the car outside the dance hall. The police caught us. They were nice about it though, giving us the choice of two fines, “drinking while under age” or “drinking in a public place.” Both fines were for the same amount. We chose “drinking in a public place.”

The frost came and tobacco picking ended. Grant and I caught a bus to Christchurch where I answered an ad for Nassella Tussock grubbers. The Nassella Tussock is an imported tussock grass originally planted along the Waipara River banks to control erosion. It spread around the North Canterbury Plain, choking out good grazing grass. The Regional Pest Management Society was hiring gangs of men with hoes to roam the hills and valleys grubbing out the tussocks. I joined one of those gangs. It was great exercise, more pleasant than picking tobacco.

Evenings, Sundays, and rainy days back at the camp were entertaining. A fellow grubber had been a culler. He told of shooting deer and feral goats and pigs. He would cut off the tails to collect the bounty on them, leaving the carcasses to rot. As well as the Nassella Tussock grass, New Zealand had a problem with non-native animals multiplying excessively.

Nassella Tussock grubbing was a job that the government arranged for convicts getting out of prison. There were a number of ex-cons at the camp. One ex-con, while in prison, used to tattoo fellow inmates—anyone who wanted a tattoo. My roommate, on hearing this, wanted a tattoo. So he lay on his back on a dining room table drinking lots of beer to prepare for the ordeal while the cook drew a tiger on his chest. Then the ex-con set to work tattooing, using a needle and thread that I had lent him and a bottle of ink. Perspiration was dripping off my roommate’s forehead. Finally he couldn’t take the pain any longer and asked if the tattoo could be finished the following evening.

The next morning my roommate didn’t get up to go to work. He was sick. When I returned from work at the end of the day, he and his belongings were no longer in our room. I learned that he had been taken to hospital with blood poisoning. In the hospital they discovered that he was AWOL (away without leave) from the army. After the hospital he was going to be sent to a military prison. I wonder if he still has a half-finished, lopsided tiger on his chest.

After quitting Nassella Tussock grubbing, I returned to Christchurch. On my twenty-first birthday I was in a pub with some friends. I hadn’t told anyone that it was my birthday as it was the custom, so I was told, for the birthday boy to buy drinks for his friends. The pub manager came up to me asking if I was of drinking age. This was late afternoon. (I know that it couldn’t have been evening as pubs closed at 6 p.m. in those days.) I had been born in the morning seventeen time zones away. In Port Arthur it was still night. So I was a few hours short of turning 21! When under interrogation it is not good to be hesitant. “Yes,” I asserted. He believed me.

I decided to travel on to Australia. The Oriana would be sailing from Wellington in six week’s time, so I returned to the North Island, got a temporary job in Wellington packing up the contents of a textile factory that was moving, then sailed for Sydney. I had to smuggle out all the New Zealand pounds that I had saved as we were supposed to take only a limited amount of New Zealand currency out of the country.

After a few days in Sydney I caught a bus to Surfers Paradise in Queensland. I didn’t surf but I did work mixing mortar for bricklayers building a hotel. It was in Surfers Paradise that I met a nice Kiwi girl on holiday in Australia. We parted ways when she had to return to New Zealand but I wanted to see more of Australia. Looking back on it now, New Zealand wouldn’t have been a bad country in which to have lived for the rest of my life.

Hitchhiking north from Surfers Paradise, I was picked up by a Pommy. That’s what Aussies call an Englishman. We were both looking for work, and found work in Yungaburra, North Queensland, helping build a plywood mill. Payday was a time for celebration. In Australia, unlike New Zealand, pubs closed late in the evening. After pub closing this particular evening, I remember helping my friend, with the bartender under his other arm, to his car. Then he drove us back to the boarding house where we were staying.

After Yungaburra, I travelled around Queensland before heading for the outback. Hitchhiking in the outback is difficult as towns are few and far between and most vehicles travelling a fair distance are already full. I was later to meet an American who told me he had camped outside Mt. Isa for eight days. Each day a tour bus would pass him. He could overhear the tour guide telling the tourists, “This hitchhiker has been here five days.” Then, the next day, “This hitchhiker has been here six days.” Then . . . .

I caught a ride that first day from Mt. Isa to Camooweal bordering the Northern Territory. The next day, waiting beside the highway outside Camooweal, I got picked up by a Canadian with his Aussie girlfriend. However, they weren’t going far. They were going spelunking near Camooweal, and invited me to join them.

We descended by rope into a hole in the ground. It was nice and cool down there, compared to the heat on the surface. The rope was just for the first part. We climbed without ropes down to the water table level. The Aussie went swimming, inviting me to join her. I declined. The water was cold! On the ascent I was longing to return to the surface where it was nice and warm.

I slept that night on the porch of one of the two pubs in the town. That was after closing. Before closing, I was entertained, for example, by one of the locals vomiting over the railings of the porch, projecting his vomit at least three yards before it hit the ground.

The third evening I hung out at the other pub. Beside it was a petrol station where vehicles filled up before travelling on. At the pub I met a somewhat inebriated man with his German Shepherd. He was also wanting to travel on. Both of us would stagger out to ask for a ride when any vehicle stopped at the petrol station. No one gave us a ride, and that without them even knowing that there were actually three of us, not just two.

My new friend said he had a taxi driver friend in Tennant Creek, which I later learned was three hundred miles down the road. He phoned him. Yes, he would come and pick us up. About four hours later he arrived. On learning that there was a dog also, he refused to take us. But my friend was persuasive. The tax driver relented, saying that if the dog got sick he would be charging extra. “Extra?” I wondered as the dog and I got in the back of the taxi. I had thought this was a friendship arrangement—a free ride.

The dog did get sick. The taxi driver did charge extra. My friend didn’t have any money, having spent the last of it on beer and the long distance phone call to Tennant Creek. I didn’t have any option. I paid. No worry, my friend told me, we could earn big money at Peko Mines near Tennant Creek. So we went there. I got hired as mill operator in the mill on the surface. We were milling copper ore. It was hot and noisy there in the mill. At that time only sissies wore ear protection. My hearing got permanently impaired.

At Peko Mines there were about four hundred of us “lonely bachelors” as we were described in a newspaper article in South Australia. A sheila, as Aussies call a woman, responded in a letter to us there at the mine saying she would be willing to come to keep us company if she could get to Tennant Creek. Raffle tickets were sold to almost everyone at the mine to raise money for her airfare. The lucky winner, however, was one of the few men who already had a girlfriend in Tennant Creek. So he sold his ticket to the highest bidder.

I worked six months at Peko Mines, long enough to claim the tax discount for working in the Northern Territory. Then I travelled on, first visiting Alice Springs from where I sent postcards to friends and relatives in Canada and England. Heading back north, I got stuck for a while, along with three other hitchhikers, at Three Ways. Finally a truck stopped. The driver bargained with us—£10 for a ride to Darwin in the back of the truck. We agreed.

In Darwin I got a job with Qantas Airways. Pilot? No, dishwasher. The job was mostly washing dishes from the various planes on their Darwin stopover. At that time airline companies served meals on proper plates with silverware and real glasses. The dirty dishes, and plates of food that hadn’t been served at all, were taken off the planes and new plates of food provided. All food that was taken off the planes was incinerated—government regulation because of the possibility of introducing unwanted parasites or something into Australia.

The new Qantas barracks were the nicest in town, but we didn’t have a kitchen and dining room there. When we didn’t eat at the airport, we ate at the Commonwealth barracks across the street from the Qantas barracks. At the Commonwealth barracks various government officials lived and ate. At a table where I often sat, I shared my dream of working on a ship to see more of the world. A customs official told me that the captain of a Norwegian oil tanker in port right at that moment was looking for extra crew members. When it came to taking action to realize my dream, I was hesitant. If I stayed two years with Qantas I could get a discount on air travel. I didn’t go to see the captain.

The next day at lunch the customs official asked me if I had seen the captain. “No.” He said the captain was still looking for extra crew members. So I went to see the captain. I got hired. I returned to the Qantas barracks and packed up my things, also letting the Qantas office know that I was quitting. Early the next morning I was on board the M/T Marie Eline. Breaking out of a comfortable rut can be traumatic. As we sailed away my hands grasping the ship rails were trembling.

I was hired as an oiler or greaser in the engine room. But my main job was helping paint the engine room. We started at the top. The top of the engine room is the hottest part of the engine room. The engine room is the hottest part of the ship. The vicinity of the equator is the hottest part of the world. It was hot!

We stopped in Balikpapan, Indonesia, to pick up oil. I joined the Norwegians going into town in the evening. They drank imported beer whereas I tried the local brew which was a lot cheaper. However, it tasted awful. Consequently I didn’t drink much. Consequently I wasn’t so drunk. Consequently I could bargain with the taxi driver who was taking us back to the ship so we didn’t get ripped off as much as we might have otherwise.

From Balikpapan we headed north as though we were going somewhere other than Singapore. At that time relations between Indonesia and Singapore were strained so we weren’t supposed to take Indonesian oil to the refineries in Singapore. But then we turned around and headed south around Borneo as that was the shortest way to Singapore.

When we sailed from Singapore, my Kiwi cabin-mate was not in our cabin. In fact, he was not on the ship. He had missed the boat. We sailed back to Borneo, but this time to Miri to pick up oil. On our return to Singapore, my cabin-mate was taken onto the ship by the Singapore authorities, having spent the time while we were away in jail. He had missed the sailing, being too much involved with a nice Singapore girl.

I had decided to leave ship in Singapore as the M/T Marie Eline was sailing to the Persian Gulf whereas I wanted to see more of the Far East. The first mate had to spend half a day with me at various offices ashore before I was allowed to disembark.

Apart from my stay on the Norwegian oil tanker, Singapore was my first experience alone in a non-English culture. It was somewhat of a culture shock, even though Singapore has a strong British heritage. Shop owners picked up on my naivety. They would invite me into their shops to look around even though I had said that I wasn’t planning on buying anything. When inside, I accepted their occasional offer of a free soft drink. That made me feel obliged to buy something in return for their favour. After a few years of travelling, I would become more cynical and write as one of my Tips for Travellers, ”When passing street vendors or shop owners in the doors of their shops, don’t let them catch your eye. Turn your attention elsewhere.”

One of the requirements before being allowed to stay in Singapore was to buy a ticket out of Singapore. I bought a ticket to Japan on the Laos, a Messageries Maritimes cargo/passenger ship. The return portion of the ticket was on another Messageries Maritimes ship leaving Yokohama a month and a half later.

We sailed from Singapore to Saigon. This was in 1965, during the Vietnamese war. At that time the main influence of the war on Saigon was the great influx of foreigners in the city. There was a curfew that lasted only for the evenings. At midnight, I think it was, people were again allowed out on the streets. I spent the evening with a couple of Kiwis from the ship in a bar in Saigon. The girls hanging around the bar pressed us to buy drinks for them. We refused, knowing that they would be served only coloured water. After a while the girls ignored us. At midnight, or whenever it was that the curfew was lifted, we returned to the ship.

From Saigon we sailed to Hong Kong. When showing slides of my travels and showing street scenes of Hong Kong, people sometimes ask what the special occasion was. They think there must have been a celebration or something for the sidewalks to be that crowded. “No,” I tell them. “That’s just the way it is.”

From Hong Kong we sailed for Kobe, Japan, where I disembarked. I remember my first meal at a sidewalk café, being given disposable chopsticks. At first I thought it was just one stick but it was two joined together. In order to use them, they needed to be broken apart. So I learned how to eat with chopsticks.

I didn’t try hitchhiking in Japan as the Japanese weren’t familiar with it. A fellow traveller told me that when he and his friend were hitchhiking in Japan a man picked them up who couldn’t speak English. They pointed out on a map where they wanted to go and he drove them there. Actually they were wanting to go right across Japan and had just picked out the next town on the map. They wondered if he was going further. They pointed on the map to the next town. He drove them there, then on to the next town where the two got out of the car. They had realized that he was driving out of his way for them.

I caught a train to Kyoto, arriving late in the evening. No one at the train station spoke English. Finally an English-speaking lady was summoned. She took me to a rooming house for foreign students where I ended up staying for most of the time that I was in Japan. It was not only the beauty of the city that held me there, but the high cost of travelling and, more subconsciously, my tendency to hang on to something that was somewhat familiar.

I remember my first time at an ofuro, a public bath. One of the students at the rooming house where I was staying had earlier pointed out the men’s door to the ofuro. I went through that door. There I encountered some Japanese women. Had I gone through the wrong door? No, they were collecting the admission fee and renting towels and selling soap to those who hadn’t brought their own towels and soap. Where was I to undress and leave my clothes? There by some shelves near the admission booth. I felt self-conscious undressing in front of the women but they discreetly looked away.

Then I went through a glass door to the first chamber where I washed myself and rinsed off the soap by pouring water over myself with a bowl. Then I entered the bath area. The bath was a large semi-circular pool. At one time it had been a circular pool but a wall had been built bisecting it. On the other side of the wall was the women’s pool. A dozen or so Japanese men, up to their necks in the bath, watched me as I tested the water. It was hot! My foot, when I withdrew it, was red. I had been told that easing in was easier than rushing in. I tried easing in but got only as far as my knees before rushing out.

In a corner of the room was a bath of icewater. I couldn’t waste my admission fee by only having washed myself. I got into the bath. It was cold! After a while the thought of going into the hot pool was very appealing. I got out and easily waded into the hot pool right out to my neck, joining the dignified Japanese men. After a while I began feeling a bit too hot. Moving would disturb the slightly cooler layer of water on the surface of my skin. But I couldn’t stand it any longer. I rushed out and jumped into the icewater. Nice and cool! After a while I felt too cool. I returned to the hot pool. After a while I felt too hot. I returned to the cool tub. The third time time that I returned to the hot pool all the other men left en mass. I wondered if I had offended them somehow, or if it was closing time or something. Now I think that they couldn’t control their laughter and it didn't want me to see them laughing.

A few days before my ship was due to sail from Yokohama, I took the train to Tokyo, staying in a youth hostel there. Through various connections, I ended up hanging around with some university students. Students were often wanting to practise speaking English, particularly young schoolgirls who often also wanted to have their photo taken with me. The university students introduced me to the Japanese Canadian who had been to the Vancouver School of Art with my cousin and his friend.

I boarded the SS Viet-Nam in Yokohama and we sailed first to Hong Kong, then to Manila, then to Saigon, and on to Bangkok, Thailand. I disembarked in Bangkok, forfeiting the Bangkok to Singapore portion of my ticket. I was planning on joining some fellow travellers going to a Thai beach to celebrate Christmas.

It was in Bangkok that I had my first experience smoking hashish. Afterwards, on our way back to the Thai Song Greet Hotel where we were staying, I got separated from the others when they crossed a busy street to catch a bus on the other side. I hesitated, finding it difficult to judge how much time I needed to dash across the street in front of approaching traffic. The bus left without me. Then I got worried—paranoid to be exact. I thought men were following me, wanting me to lead them back to our hotel. I determined not to betray my friends.

The taxi which I caught was involved in a fender-bender. Naturally I thought it was purposeful. That solidified my resolve not to return to our hotel. So I spent the rest of the night in another hotel, sitting in a chair in my room as, for a reason I don’t remember, I didn’t want to use the bed.

I spent the next day eluding the men who I thought were following me. By the end of the day I thought I had eluded them, or else my paranoia had worn off. I returned to our hotel to find only my luggage in the room. The others had left for the beach. Since I couldn’t remember which beach it was that they were going to, I abandoned the idea of joining them.

The next morning I caught a taxi to the airport north of Bangkok. From there I planned to hitchhike north. However, hitchhiking proved difficult. Thais weren’t accustomed to hitchhikers. When going to the airport terminal to use the facilities there, I got talking to a young Thai who could speak English. “Isn’t this a special day for you Christians?” Responding to my puzzled look he continued, “Isn’t it Chris....” Only then did I realize it was Christmas.

The young Thai invited me to his home after his working day was over. The next morning I accompanied him back to the airport and again stationed myself by the highway heading north. This time I got a ride.

spirit house in Thailand

spirit house in Thailand

Another experience which I now realize had some significance was being picked up, when I was hitchhiking, by a missionary on a motorbike. Through him I got addresses of missionaries along my route north. In one town I didn’t even have to ask for the address. I was led to the missionary home by a non-English speaking Thai who knew that they spoke English.

The missionaries taught me some Thai ethics, such as not pointing my foot at anyone, even unintentionally as I might if sitting cross-legged. Jim, an Irish missionary, warned me not to try contacting spirits. Like many Thai Buddhists, I believed in spirits.

I spent a few days in Chiang Mai before returning to Bangkok. Back in Bangkok, I thought I might as well visit Cambodia before continuing my travels westward. I caught a train to the border, then walked across. There were strained diplomatic relations at that time between Thailand and Cambodia, so there was no public transportation across the border.

The missionaries taught me some Thai ethics, such as not pointing my foot at anyone, even unintentionally as I might if sitting cross-legged. Jim, an Irish missionary, warned me not to try contacting spirits. Like many Thai Buddhists, I believed in spirits.

I spent a few days in Chiang Mai before returning to Bangkok. Back in Bangkok, I thought I might as well visit Cambodia before continuing my travels westward. I caught a train to the border, then walked across. There were strained diplomatic relations at that time between Thailand and Cambodia, so there was no public transportation across the border.

Angkor, Cambodia

Angkor, Cambodia

I stayed that night in a hotel in Siem-Reap. One of the hotel workers who could speak a little English seemed to envy us Westerners. He seemed to think there was an unfair discrepancy between living standards in the first world and the third world. That attitude was similar to that of Pol Pot and the Kmer Rouge, with which that young hotel worker might have later teamed up. The Kmer Rouge was in its infancy at that time, but was soon to become popular. Nowadays, most Cambodians would say the Kmer Rouge were wrong, and most Buddhists would say the same. Part of the Buddhist Noble Eightfold Path is right intention and right conduct.

I teamed up with a fellow Canadian also staying at the hotel. We rented bicycles and toured the temples of Angkor. The next day we caught a train to Phnom-Penh and the day after that another train back to Siem Reap to resume the discussion with the disgruntled hotel worker.

Back in Bangkok, I investigated the possibility of travelling overland through Burma. No possibility. The cheapest way to get to India was to fly with Union of Burma Airways with a student discount.

In my passport, the line for Occupation/Profession was blank. Years earlier, when I had applied for a passport in Canada, I had left that line blank on the application form. Having become a wiser traveller, I could see the advantage of being a student. I went to the British Embassy in Bangkok which at that time handled Canadian affairs. Actually I had gone to the embassy the day when I was paranoid and trying to elude the men I thought were following me. I had seen the Canadian vice-consul, I think he was, and explained the situation as I saw it. He had advised me to leave the country as soon as possible. Now he was authorizing the filling in of “student” for Occupation/Profession.

With my passport I went to the Union of Burma Airways office and got a ticket, student fare, from Bangkok to Calcutta, with a stopover in Rangoon. On the plane I met a couple of young Englishmen who had got a bunch of student cards printed in Bangkok. They gave me one, which came in handy later. Travelling student rate meant that overnight accommodation wasn’t included. Tony, Dennis, and I slept the night on table tops in the Union of Burma Airways office in Rangoon. Mosquitos made the night yet more uncomfortable.

On the plane also was a lovely Aussie girl, Gail by name. She spent the night in a hotel with other non-student-rate passengers. When arriving in Calcutta, the four of us teamed up to go to the Salvation Army Hostel which we had heard was a good place to stay. I remember travelling to the hostel by rickshaw. Instead of hiring four rickshaws, we hired just two, paying a little extra for piling two people, with our luggage, in each rickshaw. It was a hard haul.

The Salvation Army Hostel was luxurious. I remember enjoying a proper English breakfast which included toast and marmalade. Local meals were often chapattis and dal, spiced up so as not to be so bland. Being unaccustomed to such hot food, I would be eating chapattis and dal with tears running down my cheeks.

The four of us decided to go to Nepal. We caught a train—third class with student reductions—to Benares, also known as Varanasi, on the Ganges River. We watched pilgrims bathing in the Ganges, probably emerging dirtier than when they went in. On the banks of the Ganges bodies were being burnt. We watched one which seemed to be more of a slow cook. I guess the man cremating his mother, perhaps—a small bundle perched on a pile of wood the size of a campfire—might not have had the money to buy lots of firewood. Another man came and borrowed a flaming stick of wood to light a small fire of his own with which to boil water for chai, as tea is called in India.

From Benares we continued to the Nepalese border. From there we caught a ride in the back of a loaded truck over the Mahabharat Mountain Range. Some Nepalese were also riding in the back of the truck. Some had a problem with motion sickness. Dennis warned Tony, “That bloke by your rucksack looks quite sick!” Too late. He vomited over Tony’s rucksack. Because it was so cold, Gail changed to riding in the cab of the truck.

We arrived in Kathmandu and checked in at the Globe Hotel. It wasn’t luxurious accommodation. The room wasn’t heated. The beds were bare mattresses. The toilet was a hole in the ground outside in the courtyard. We shouldn’t have expected better when we were paying the equivalent of 5¢ each per night, after changing American dollars on the black market.

Hashish was also cheap. However, never having been a smoker, I had difficulty keeping smoke in my lungs for any length of time. Also I liked to be in control of my life. Some young people had vegetated in Katmandu, seemingly with no inclination, or no money, to travel on.

I remember Gail and I pondering over the meaning of life. I envisioned events in life being interdependent, like gears within a clock causing other gears to move. Visioning the gears more closely, it seemed that many of the cogs on the gears were out of line. They weren’t meshing with other cogs the way they were meant to. And it seemed as though the cogs were living and the conflict was causing pain. Gail’s visionings were more mellow than mine.

A popular tourist excursion was climbing Mt. Nagarkot, not far from Katmandu. Early one morning Gail, Tony, Dennis and I set off by bus to the base of the mountain. Then we began our climb, deciding to climb straight up one side rather than following the road which wound its way to the top.

On we climbed, past smaller and smaller villages. Kids gawked at us. Tony made an Abominable Whiteman laugh at them and they ran away giggling. On reaching the top, we could clearly see the great expanse of the Himalayas. After checking in to one of a couple of stone buildings, we climbed to a rocky outcrop where we sat studying the mountains, comparing their outlines to a picture map that unfolded to an arm’s length. A small, snow capped peak, dwarfed by closer mountains, was named Mt. Everest. We celebrated by smoking a few joints.

We returned to the guest house, just the four of us foreigners in the house. The neighbouring house was where some Nepalese lived and where we would be eating supper and breakfast. Ours was a comfortable house. We even had a sit-down flush toilet! luxury compared to the hole in the courtyard back at the Globe Hotel into which, incidentally, I accidentally fell one night when I was high.

We were called to come for supper. Sitting on bench seats around a table, we were served a delicious hot meal. Our servers waited beside a roaring fireplace. The room was nice and warm.

But I couldn’t allow myself to get drowsy! Paranoia had set in. Here we were so vulnerable. They could easily overpower us and rob us, or even . . . ! Who would know? Did anyone back in our respective countries even know where we were? I had sent a postcard home from Calcutta but had I mentioned that I was thinking of going to Nepal?

We were served tea, but there seemed to be a problem. The Nepalese were conferring with one another in hushed voices, not that I could have understood them if they had spoken out loud. Then one man put on his coat and hurried out the door. One or two of my companions sipped their tea. I didn’t—our hosts may have been trying to drug us.

After a while the man who had left so hurriedly returned. Then they brought us chunks of sugar, as usual in many Asian countries, broken off from a larger block. “How sweet!” Gail commented. “That man must have gone quite a distance down the mountain just to get us sugar.” I wasn’t convinced. I didn’t touch my tea.

After supper we returned to the guest house. There was no door lock. The others weren’t concerned so I pretended to be unconcerned also. Sitting on beds under a dim light, we played cards, hearts to be exact. We were also smoking. I was getting more and more worried. Finally I spoke up, asking if they thought we were in danger. “Why?” I explained. They laughed. Finally they convinced me that it was all in my imagination. The Nepalese are nice people, not just because we were paying them for their services. They were nice just because it’s nice to be nice. I slept in peace that night.

After breakfast the next morning, we trekked back down the mountain. We were wondering if we were heading in the right direction for the bus stop at the base of the mountain. A boy gave us an Abominable Whiteman laugh. We felt assured.

I teamed up with a fellow Canadian also staying at the hotel. We rented bicycles and toured the temples of Angkor. The next day we caught a train to Phnom-Penh and the day after that another train back to Siem Reap to resume the discussion with the disgruntled hotel worker.

Back in Bangkok, I investigated the possibility of travelling overland through Burma. No possibility. The cheapest way to get to India was to fly with Union of Burma Airways with a student discount.

In my passport, the line for Occupation/Profession was blank. Years earlier, when I had applied for a passport in Canada, I had left that line blank on the application form. Having become a wiser traveller, I could see the advantage of being a student. I went to the British Embassy in Bangkok which at that time handled Canadian affairs. Actually I had gone to the embassy the day when I was paranoid and trying to elude the men I thought were following me. I had seen the Canadian vice-consul, I think he was, and explained the situation as I saw it. He had advised me to leave the country as soon as possible. Now he was authorizing the filling in of “student” for Occupation/Profession.

With my passport I went to the Union of Burma Airways office and got a ticket, student fare, from Bangkok to Calcutta, with a stopover in Rangoon. On the plane I met a couple of young Englishmen who had got a bunch of student cards printed in Bangkok. They gave me one, which came in handy later. Travelling student rate meant that overnight accommodation wasn’t included. Tony, Dennis, and I slept the night on table tops in the Union of Burma Airways office in Rangoon. Mosquitos made the night yet more uncomfortable.

On the plane also was a lovely Aussie girl, Gail by name. She spent the night in a hotel with other non-student-rate passengers. When arriving in Calcutta, the four of us teamed up to go to the Salvation Army Hostel which we had heard was a good place to stay. I remember travelling to the hostel by rickshaw. Instead of hiring four rickshaws, we hired just two, paying a little extra for piling two people, with our luggage, in each rickshaw. It was a hard haul.